Key takeaways:

- A subordinate clause, or dependent clause, cannot stand alone as a complete sentence and relies on a main clause for meaning.

- Subordinate clauses begin with subordinating conjunctions or relative pronouns and provide additional information to a sentence.

- Understanding the differences between subordinate and independent clauses helps with correct punctuation and sentence structure.

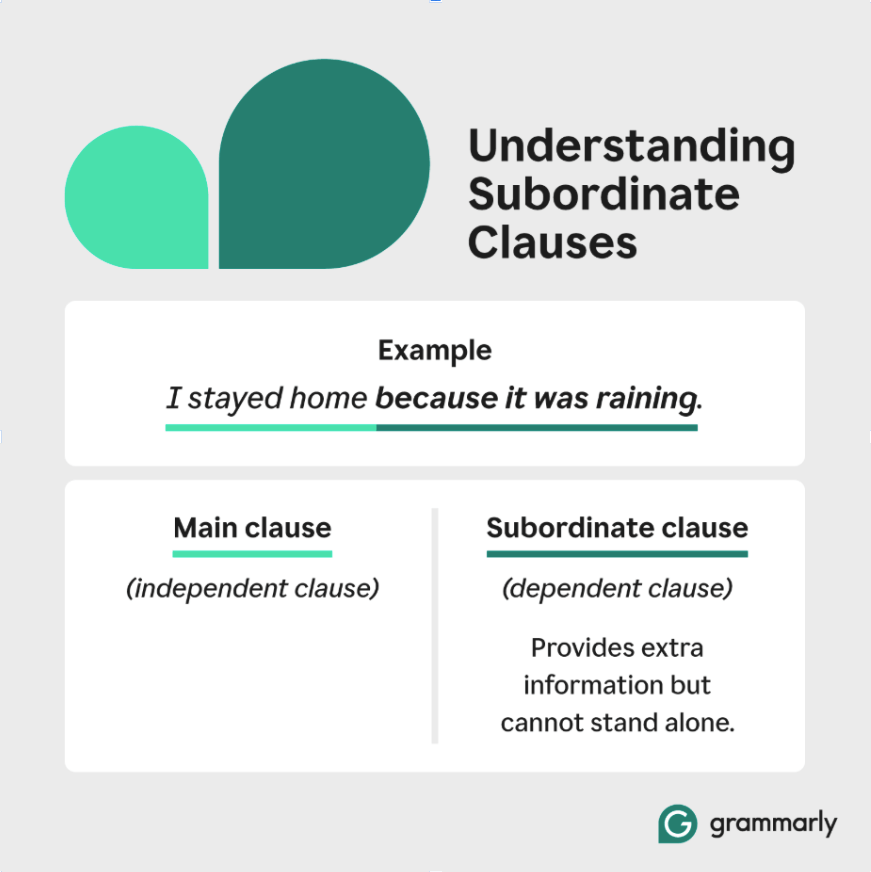

A subordinate clause, or dependent clause, cannot stand alone as a complete sentence. It relies on a main (independent) clause to make sense.

You might hear both terms—subordinate clause and dependent clause—but they mean the same thing. Unlike subordinate clauses, independent clauses can stand alone as complete sentences. A subordinate clause adds information to the main idea but can’t stand alone—for example, “because the lights were off.”

In this post, we’ll break down how subordinate clauses work, why they matter, and how to use them correctly in sentences.

Table of contents

Subordinate clause vs. main clause

Words that begin subordinate clauses

Examples of subordinate clauses

Why do I need to know which clauses are subordinate?

Comma placement: Restrictive vs. nonrestrictive clauses

Subordinate clause vs. main clause

Whether you call it a subordinate or dependent clause, its job is to add extra information to the main part of the sentence. This main clause will be independent: It can stand on its own as a complete sentence.

Independent clause: We can all go for ice cream.

This sentence is an independent clause. It has a subject and a verb, and on its own, it presents a complete unit of meaning: All of us can go out and have ice cream. (Hooray!)

But what if going for ice cream was dependent on something else?

Independent and subordinate clause: We can all go for ice cream if I can find my wallet.

If I can find my wallet adds substantially to the meaning of the sentence. It is too soon to celebrate our ice cream outing because there is a task at hand. We have to first find that wallet.

On its own, “If I can find my wallet” is a subordinate clause because it is not a full unit of meaning. If it were written separately as a sentence, the result would be a sentence fragment—a frequent mistake.

Subordinate clause: If I can find my wallet.

What will happen if I can find my wallet? If a clause in your sentence structure leaves us hanging like this when set apart on its own, it is a subordinate clause.

Types of subordinate clauses

Let’s explore three common types of subordinate clauses: adjective clauses, noun clauses, and adverb clauses.

Adjective

An adjective clause modifies or describes a noun in the main clause. These clauses usually begin with relative pronouns, such as:

- Who

- Whom

- Whose

- Which

- That

They provide additional details about the noun they modify.

Example: The book that she borrowed from the library was fascinating.

Noun

A noun clause functions as a noun in the sentence. It can act as a:

- Subject

- Object

- Complement

Noun clauses often begin with words like:

- What

- Who

- How

- That

- Whether

Example: What he said surprised everyone.

Adverb

An adverb clause modifies a

- Verb

- Adjective

- Another adverb

It explains how, when, where, and why something happens. These clauses are typically introduced by subordinating conjunctions such as:

- Because

- If

- When

- While

Example: She stayed home because she was feeling unwell.

Words that begin subordinate clauses

Subordinate clauses will often begin with subordinating conjunctions, which are words that link dependent clauses to independent clauses, such as:

Subordinate clause words by function

| Category | Subordinating Conjunctions |

| Time | When

While Before After Since Until Once |

| Cause | Because Since As |

| Condition | If Unless Provided that |

| Place | Where Whenever |

They can also begin with relative pronouns such as:

- That

- Which

- Who

- Whom

- Whichever

- Whoever

- Whomever

- Whose

Relative pronouns introduce the subordinate clause and connect it to the noun in the main clause. Spotting these words can tip you off that you’re dealing with a subordinate clause rather than a main clause.

Examples of subordinate clauses

Subordinate clauses provide additional information but need a main clause to complete a thought. They often begin with subordinating conjunctions like:

- Because

- Although

- If

- Since

- While

Below are some examples of how they function in sentences.

Subordinate clause examples

| Sentence example | Subordinate clause |

| She missed the bus because she was running late. | because she was running late |

| They went for a walk although it was raining. | although it was raining |

| If you finish your homework, you can go outside. | if you finish your homework |

| We haven’t seen him since he moved to the city. | since he moved to the city |

| The storm hit while they were sleeping. | while they were sleeping |

Comma placement: Restrictive vs. nonrestrictive clauses

Punctuating subordinate clauses that begin with relative pronouns can be tricky, such as:

- That

- Which

- Who

- When

- Where

- Whose

These are also called relative clauses. There are two types of relative clauses: restrictive and nonrestrictive.

Restrictive clauses: No commas needed

Restrictive clauses are sometimes referred to as essential clauses. This is because they are essential to the meaning of the sentences they are a part of. Do not set essential elements of a sentence apart with commas.

Example: I enjoy watching movies that employ lots of special effects.

Nonrestrictive clauses: Use commas

You can remove nonrestrictive clauses from a sentence without changing its main meaning. Since they are nonessential, you should always set them apart with commas in a sentence.

Often, nonrestrictive clauses will “interrupt” a main clause, as in the example below, and when that happens, you should insert a comma both before and after the clause.

Example: Watching Star Wars, which has lots of special effects, is my favorite thing to do.

Without the nonrestrictive clause, “which has lots of special effects,” the core idea of the sentence, “Watching Star Wars is my favorite thing to do,” is still intact.

Simplify subordinate clauses

Understanding subordinate clauses can elevate your writing by adding extra details to otherwise complete sentences. While they may seem complex at first, with practice and the right guidance, you’ll quickly incorporate them into your sentences with ease.

Write with confidence using Grammarly

Writing subordinate clauses correctly can be tricky, but Grammarly makes it easy. It provides instant feedback on grammar, spelling, punctuation, and more. Try Grammarly today for free to ensure your writing is clear and mistake-free.

Subordinate clause FAQs

Below are frequently asked questions about how subordinate clauses work, helping you understand their structure, function, and proper use in English grammar.

Why do I need to know which clauses are subordinate?

Understanding subordinate and independent clauses is crucial for grasping punctuation rules and comma usage. By distinguishing between the two, you can determine when a comma is necessary and avoid common mistakes.

When a subordinate (dependent) clause begins a sentence, it should be followed by a comma.

- Incorrect: If I can find my wallet we can all go for ice cream.

- Correct: If I can find my wallet, we can all go for ice cream.

When a main (independent) clause starts the sentence, no comma is needed before the subordinate clause.

- Incorrect: We can all go for ice cream, if I find my wallet.

- Correct: We can all go for ice cream if I can find my wallet.

Following these punctuation rules helps you write clearly and avoid comma mistakes, making your writing flow smoothly.

How do I identify a subordinate clause in a sentence?

To identify a subordinate clause:

- Look for a group of words that contains both a subject and a verb.

- Check if it can stand alone—a subordinate clause cannot be a complete sentence on its own.

- Determine if it forms a complete thought. If it leaves you with an incomplete idea, it’s a subordinate clause

Can a subordinate clause stand alone as a sentence?

No, a subordinate clause can’t stand alone as a sentence because it’s not a complete thought. It is dependent on the main (independent) clause to provide context and meaning. For example, “because it was raining” needs more information to form a complete sentence.

What’s the difference between a subordinate clause and an independent clause?

An independent clause expresses a complete thought and can function as a stand-alone sentence. In contrast, a subordinate clause contains a subject and verb but relies on an independent clause to complete its meaning.

For example, “She smiled” works as an independent clause because it presents a complete idea, whereas “because she was happy” is a subordinate clause that needs additional information to make sense on its own.